Article by: Ar. Alan Kor Loong Lau Published on: Intersection Newsletter May 2020 Issue

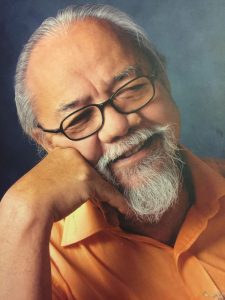

Visiting Raphael Scott Ahbeng at his Bau house was like visiting a favourite elderly uncle. Walking with the aid of a stick, he greeted me warmly like an old friend, even though we had only ever met once before. He was genuinely delighted to have company, and he guided me through the verdant grounds. “It’s a big house, but luckily I’m not the one who has to look after it, for that I have to thank my poor wife,” he quipped.

He spread his hands gingerly, showing me his knuckles swollen with arthritis. It was a natural hazard dreaded by all painters, but Raphael bore his affliction with good humour. “Sometimes it’s so painful that I can’t paint,” he said, showing the one hint of sadness during our entire visit.

He opened the door to his studio, a free-standing bungalow where he painted and stored his art. Inside was another world, the universe interpreted by Raphael Scott Ahbeng, in dazzling line and colour. Having seen the painful state of his hands, I’m struck by how prolific he remained in later life, how vast the scale of his art. Paintings of a monumental scale hung and stacked against the walls. There were rivers, forests, valleys, and mountains, brought to life in his trademark exuberant Raphael colours. In his well-known mountains series, the trees streamed freely as rivulets of paint. In another canvas, a forest landscape became as riotous as a street parade, raining streaks in eye-popping shades.

Raphael was, and remains, Sarawak’s most famous painter of any style or age. Even a cursory look at his oeuvre will show that his single most enduring subject was Sarawak itself. Raphael was born during the Japanese Occupation, saw a brief return to Brooke rule, cession of Sarawak to Britain, and witnessed the birth of the modern state as part of Malaysia.

Raphael’s came from a large Bidayuh family of 8 children. His father packed him off to school at an early age, where he endured the harsh discipline of an austere mission education. Despite this, a visiting delegation of British Council officials noticed the well-spoken, bright young man, and eventually recommended him for a scholarship to study broadcasting in England.

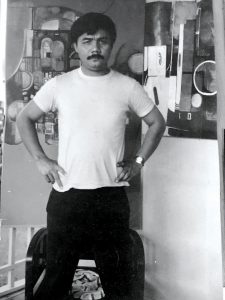

For a young Bidayuh man who had never even left the country, going to England during the 1960s must have seemed like flying to the moon. Despite the loneliness and sense of alienation, Raphael still opened himself up to the experience, garnering some deep and lasting friendships along the way. The welsh actor David Prince recalled how in 1965, “Ray” invited him to join him on a cycling tour of Europe, where they ended up being interrogated by Fascist guards in Franco-era Spain on suspicion of being spies.

After his English sojourn, Raphael returned to Sarawak and settled into a career at RTM, where he eventually became head of the English service. Throughout his career as a broadcaster, Raphael continued to pursue his passion in art and painting, which he had done from an early age. As his talent grew, so did the voices encouraging him to pursue painting full time. When the time came to leave broadcasting, he did exactly that, setting up a studio at Rubber Road.

Pursuing a painting career in Sarawak then, as it is now, was a daunting and unpaved path. Even for a man like Raphael, it must have taken real steel of soul. But a slew of early commissions, notably for the Rhiga Royal Resort and the Royal Mulu Resort, gave the impetus he needed. His daughter June recalls her father strapping 150 canvases into a single car, before driving them to Mulu himself. Through sheer talent and hard graft, his career as a sought-after painter of modern canvases took off.

Apart from his painting, Raphael loved to sketch. In contrast to his professional painting, which consisted mostly of landscapes, his pen-and-ink drawings show his acute observation of people. As he grew older, they became more like cartoons, with little snatches of dialogue and witticisms. They depict ordinary people in everyday situations – in queues at the bank, at the market, furiously politicking in coffee shops – showing a deep interest in what people on the streets felt and thought. His daughter June hopes to have them published someday, to show a lesser-known side of the artist.

But for the time being, it’s for his vibrant landscapes that we’ll best remember Raphael Scott Ahbeng, as well as his deep love of his native land. As his painting career took off, Raphael could have chosen to live and work in the big city, closer to the wheelers and dealers of the art world. Instead, he decided that if people wanted to seek him out, they would have to come to him at Bau. The man himself was inseparable from his homeland.

And so it was fitting that Raphael Scott Ahbeng, Sarawak’s most eloquent master of colour and paint, should come home to rest, not far from the place he was born. He will be remembered as a trailblazer, a brilliant artist, and a wise and wonderful human being. We are all the poorer for his loss, but all the richer for his having lived among us.