In recent months, university reviews for the architecture faculty has taken place online. Although the students have risen to the challenge and adapted to new methods of presentations and platforms of online interaction – it lacks the energy, the learning, the drama of the traditional review or ‘the crit’.

So, what is a ‘crit’?

It is a review that takes place several times throughout the course of an assignment for you to present your ideas and research, and for you to receive feedback from tutors and colleagues. For most of us, the critique is unlike any previous experience and this article is an attempt to dissect the process so that we can learn from it in school and at the office. It is written from personal observations with extracts from ‘The Crit –An Architecture Student’s Handbook by Rosie Parnell and Rachel Sara with Charles Doidge and Mark Parsons’ and ‘Time management for architects and designers by Thorbjoern Mann’.

In the initial stages of a project, this is likely to be in the form of a small discussion group with 6-8 students and the tutor. In real life, the group is likely to be made up of the architect, the client and the end user. Sometimes, an expert is called in to guide the development of the project brief such as an engineer or planner.

This is followed with a series of interim reviews when the student is expected to show their ‘work-in-progress’ in a semi-formal setting to a larger audience and get a variety of opinions. In practice, this is usually when end-user groups and specialist would offer the most feedback. In both practice and in school, the outcome of the interim review is usually the watershed moment when the main idea of the project is determined.

The final review can be the most nerve-wracking stage because you know that your work is being marked on your research, your ideas, your drawings and documentation and your oral presentation. No wonder, it is the cause of the ‘all-nighter’.

In the final review, there might be an emphasis on practising presentation skills for your future life as an architect. It is also a tremendous learning experience for the following reasons:

- Participation in review discussion can develop your understanding of architecture.

- The review allows you to hear a variety of opinions and ideas about your work.

- The review allows you to see other people’s work and develop critical thinking.

- And lastly, it is a deadline – good practice for time management for a strong finish to a project and celebration of your hard work.

Final review – speak slowly and clearly, and to the whole room.

Final review – don’t be afraid to engage with the tutors; use your props to explain your ideas.

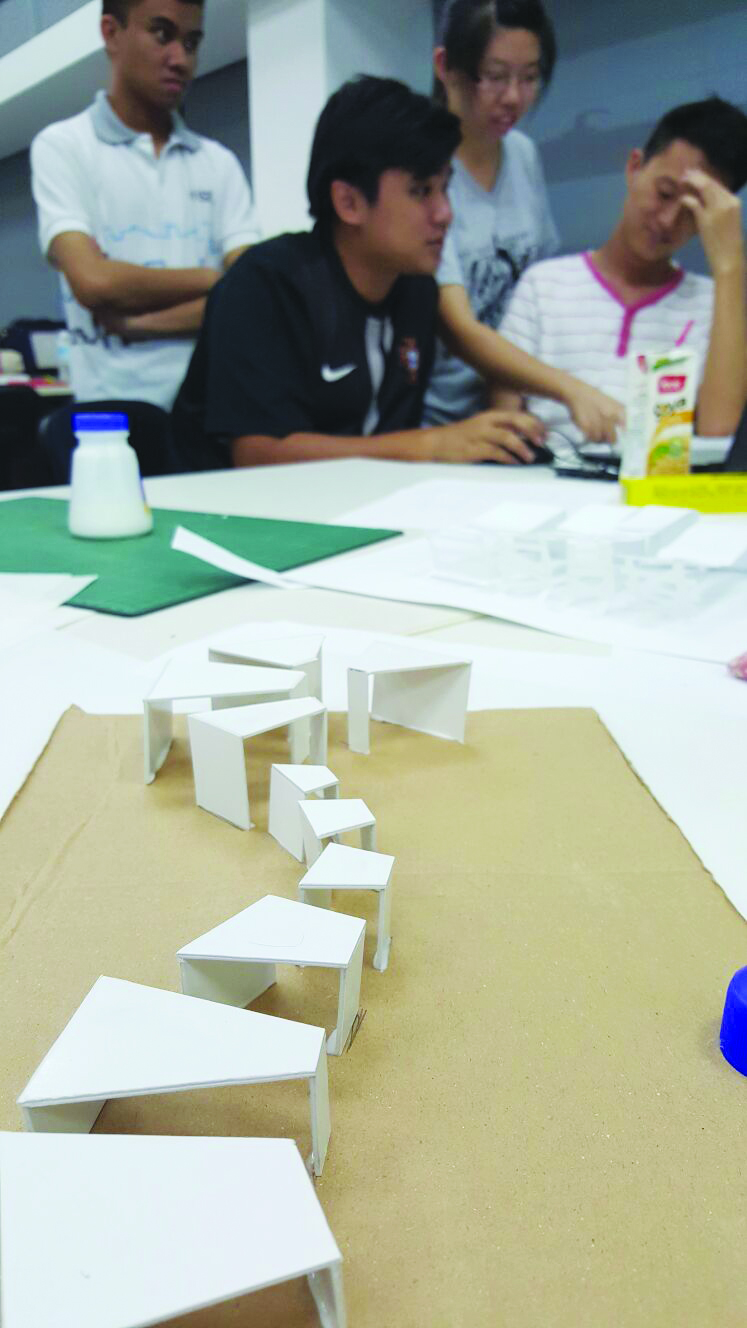

Interim crits are less formal and are usually in smaller groups.

Make use of your progress sketches and models in the final preparation.

How to prepare for the final review

Many students spend too much time preparing their drawings and models that they forget about the written and oral part of the presentation. In the final rush, the oral presentation is left to the day itself when the student expects to present ‘off-the-cuff’*

* Even speaking ‘off-the-cuff’ requires preparation, the expression is derived from an actor’s practice of having key lines written on the cuff of his shirtsleeves.

Framing the oral presentation should take place before the visual presentation – it allows the formatting of key ideas, its development and final outcome on the presentation boards. The following steps have proven useful to students and in practice:

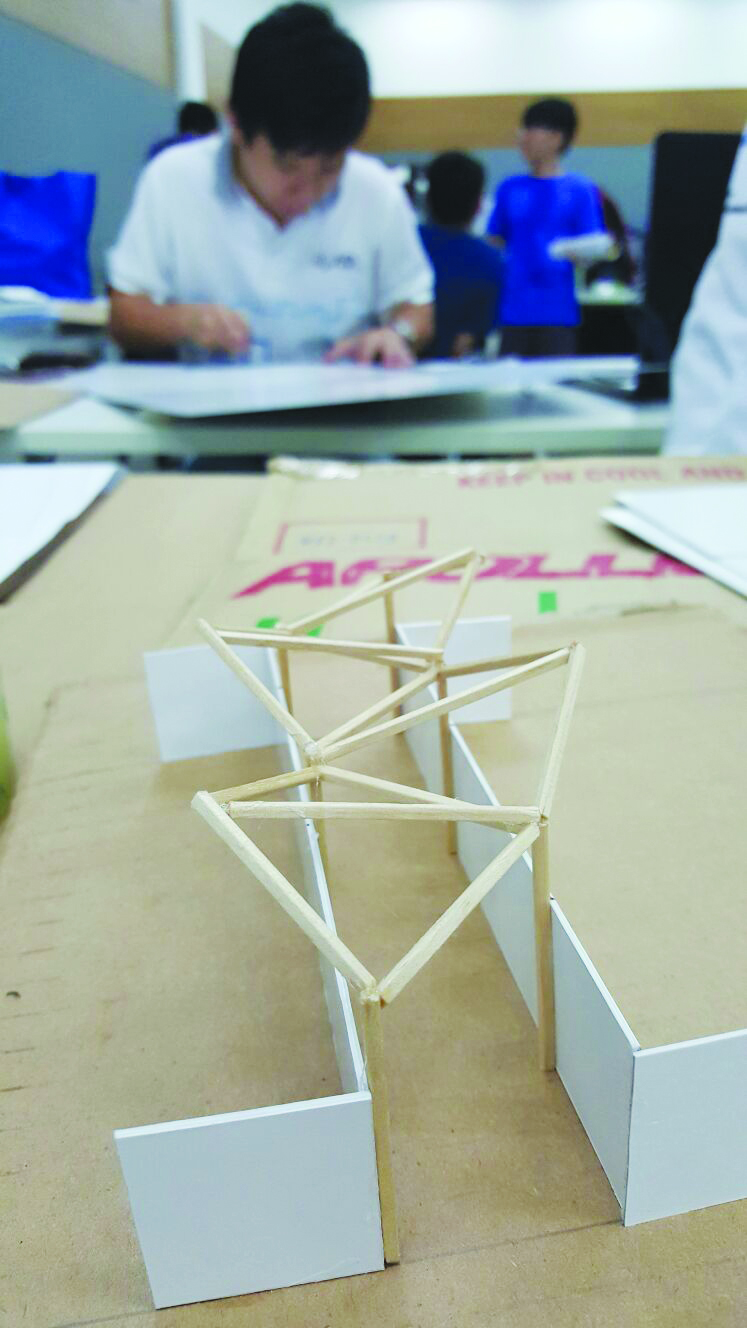

- Prepare a mock-up of the presentation boards, and models (think about how you will stage this in the room)

- Know who you are presenting to, and rehearse on a colleague (get her to pose questions so that you can frame a defence of your scheme)

- Plan your opening sentence, include key words and phrases on the boards as prompters. (Use a storyboard to sequence your presentation.)

- Include your progress sketches and models in your presentation to demonstrate your research and development. (In practice, this is useful to illustrate the ‘distillation’ of ideas to arrive at the final one)

- Things to avoid – using jargon (simple language is best), starting sentences with ‘basically’ or ‘actually’ (think about the meaning of these words), don’t start with an apology (even if your model is incomplete), don’t read from the board (speak to the audience, make eye-contact), don’t speak too casually (you are practising for practice), speak slowly, end confidently and conclude with a ‘thank-you’.

What do we get from a review

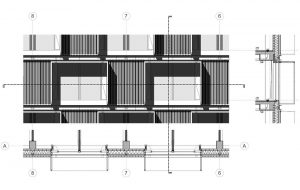

From your own review, feedback could cover general principles about architectural design, construction details, drawing and presentation techniques, model making, physical posture and vocal performance

An important point to remember here is that we can learn from other people’s reviews as well as our own. This is best done through 3 simple ways:

- Observation – to develop your skills in critical analysis and your understanding of architecture. Make sure you can see what is being discussed, go up to the work and take a close look.

- Listening – take down keynotes while listening, to return to them for future reference.

- Participate – other than simply observing from the back of the room, get involved in the discussion, and ask offer constructive criticism.

Special note about constructive criticism (extracted from ‘The Crit’)

There are a few rules to bear in mind when offering feedback to someone else:

- Identify something specific you like about the project presented. We all need to be told when we are doing well and yet this is rare.

- Express negative criticism as specific changes and ideas for action. It’s easier to work with specific ideas than general comments.

- Explain the purpose of any questions you ask. It’s easy to interpret an unexplained question as an attack.

The all-nighter – a common phenomenon in architecture schools.

The university offers a safe place to make mistakes.

What to expect from your tutor

He might have a lot feedback as he has seen your work through its development, and his role is not to support you. He might step in if he feels that your ideas are misunderstood, otherwise it is your job to stand up for yourself.

What to expect from visiting critics

It is likely that their viewpoints will be very differently from yours, be ready to listen and accept that you may not have thought of all the possible solutions. Sometimes, the client and end-users are present at your final review, their viewpoints are very valuable in broadening the debate beyond the architecture studio.

To mark or not to mark? One of the reasons for the final review is to mark the students’ work. Some educators think that this puts undue stress on the student – pinning everything on 15 minutes of oral presentation. Others feel that since the mark is based on the final review, this means that the student cannot use the feedback from the review to improve his scheme further.

Speaking as a practicing architect, I feel that the work should be marked at the final review as this is good practice for understanding the importance of deadlines in real life. Perhaps the school can allow another week after the review for final touching up and revisions for submission or exhibition – this is a good practice for curating the student as well as the school’s portfolio.

Since the pandemic, architecture schools have had to look into different types of reviews from simple PowerPoint presentations to ZOOM webinar to MIRO, who reviews can individually select and edit the presentations online in real time. I have experienced all the above and can safely say that – I can’t wait to get back into the studio!.

Having said that, I feel the review system can do with a review – in its present form it promotes some of the less attractive attributes linked with architects and designers. It needs to encourage a more rounded conversation; to teach balance and responsibility to society, to learn to listen and include the end-user in the design process and so forth.

Alternative reviews

Nowadays, clients and user-groups are becoming more involved in the whole design process. In practice, we see that client as part of the design team and we review our work collectively. This kind of review can slowly be worked into the school review system (including the interim reviews) as a

Student-led review where they learn to offer feedback. The tutor simply facilitates this process and highlight issues which might have been missed out, but does not offer feedback.

Other forms of reviews:

Role-play review where students take on roles of the client, end-users, architect which allowed them to appreciate the different and often contradictory viewpoints that an architect has to manage with perception and thoughtfulness.

Mirror review where the student explains her work to a colleague who then presents it for her – this requires distillation of ideas and clarity in the design thinking and presentation materials.

Closed review where the boards are reviewed in the absence of the student, this is often seen in design competitions where the drawings will then have to speaks for themselves.

This concluding paragraph brings me to the first point of this article – my first year students had to figure out themselves on what to present, how to format their boards and frame their presentations They had to learn the rules, sometimes only by breaking them. This article hopes to mediate the process of learning through the review.

In recent years, I have also learnt to improve my review methods. In the past, I would have said ‘the entrance to your building is in the wrong place’ (focusing on the negative), these days I say ‘tell me about the entrance to your building’ (giving the student a chance to explain an unusual decision).

by Min