In recent years this part of a student’s education takes place at the end of 2nd Year (3 months), and also at the end of 3rd Year (3 months). This format aims to help launch students into the work place, and hopefully settle into some sort of gainful employment.

In the past, internships were also called practical training or work experience, during which the student train under/with an external supervisor or mentor in the same profession. The aim is to expose the student to the practical realities of ‘practice’; to learn about dealing with people – consultants, clients and colleagues; to keep deadlines and work in a structured environment for a regular number of hours a day.

When put this way, it doesn’t sound very interesting or educational at all. It sounds more like the system is preparing them for the workforce when in fact, many (given the right mentoring) will continue their architecture education in Part 2 and beyond.

So, this article is divided into 3 Sections to list down and discuss the roles of the relevant parties:

- – The Student

- – The Mentor, and

- – The School

THE STUDENT

> Must treat this like a job application and while it is customary now to apply via email – the tone must still be formal. (Address each person you are writing to specifically, even if you are applying to a dozen firms).

Call to follow up after a few days if you have not received a reply (if the answer is ‘no’ then you can move on or update your list of firms to apply for)

Always attach your resume and portfolio without having to be asked. As ‘employers’, we are more interested in your skills, design interest/influence, preoccupations rather than your Form 5 result slip or CGPA scores.

> Your resume should be one A4 page long and include your extra-curricular activities. It should include samples of your extra-curricular activities ( If you are a volunteer fire-fighter, make sure to mention it)

* I look for these in particular and have accepted interns based on their ability to sing and raise money for charity, ability to speak Spanish and take part in exchange programmes, good in photography, sketching, any particular sport (represented school/state), etc.

> Your portfolio which should contain a few select projects that best describe you, your design interest and skills. It should be easy to download for review (Anything which takes more than a minute to download is likely to be ignored)

* This reinforces the need to start/keep a portfolio from Year 1 Semester 1.

> At the interview (if there is one) or the first briefing with the mentor, let her/him know that it is important for you to understand your role in the office. Other than the basic office rules/regulations, ask what you will be expected to do on a daily/weekly basis.

> Explain that your work has to be supervised and signed off in a logbook provided by the University. Ask to be involved in projects. (To learn about projects in various stages : schematic Design, Design Development etc)

> Ask if there is a probation period.

> Don’t be shy to ask about your allowance or salary. (You should be paid; at least enough to cover the costs of your transport and lunch)

> Important Note

Request to meet with your supervisor/mentor weekly even if it is for 20 minutes. These might be the only opportunities for you to see her/him during your internship – use these sessions to review/discuss your logbook entries.

-Too blank? (not enough work)

-Too much in the same category of work? (not enough exposure)

> Keep a separate work journal if the school does not provide one; for you record your lessons learnt. (and include examples of your work with the supervisor’s permission)

* This is similar to the logbook and report that one has to prepare in order to sit for the LAM-PAM Part 3 exams, so it is a good habit to form early in your career.

> For many students, internship will be hard at the beginning but it should also be educational and fun – if not, make use of the probation period and LEAVE.

THE MENTOR

> It is good to refresh our memories of our own internship and remember that our role is primarily one of educating and mentoring, and then to utilize the student’s time to do some productive work for the office. Getting these priorities right is important as the reverse would result in

-A poor learning experience for the student

-No more applicants for internship for the supervisor

> It is important for you to explain office/work protocols to the student, for many this is their first ‘work experience’ – punctuality, work ethics, confidentiality and copyright, etc.

* I find it easier to work with more than one intern at a time; there is a ‘team’ and they often learn from each other as well. (If they can be from different universities, even better)

> You can assign another person in the office for the interns to consult when you are not available. (This is true of larger companies where young graduates are tasked with mentoring interns. This is a good practice as it benefits both parties and as the age gap is smaller, communication is probably less formal and more productive.)

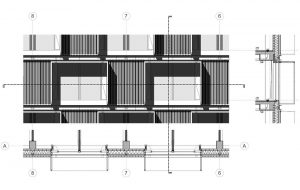

-The student needs her/his logbook to be endorsed by the supervisor. It is a good guide to expose the students to the 4 stages of a project using various projects in the office – in that way, the student receives a holistic work experience.

> You can divide their workload into:

-Projects: work-related with actual deadlines, and when done correctly will result in making money for the company (is how I explain it)

-Assignments: task-related to teaching the intern about something more obscure such as the width of staircases in relation to fire safety, or how to calculate rainfall days in EOT assessments. It is not directly related to their training in school at the present time but it certainly opens their eyes to the many facets of our profession.

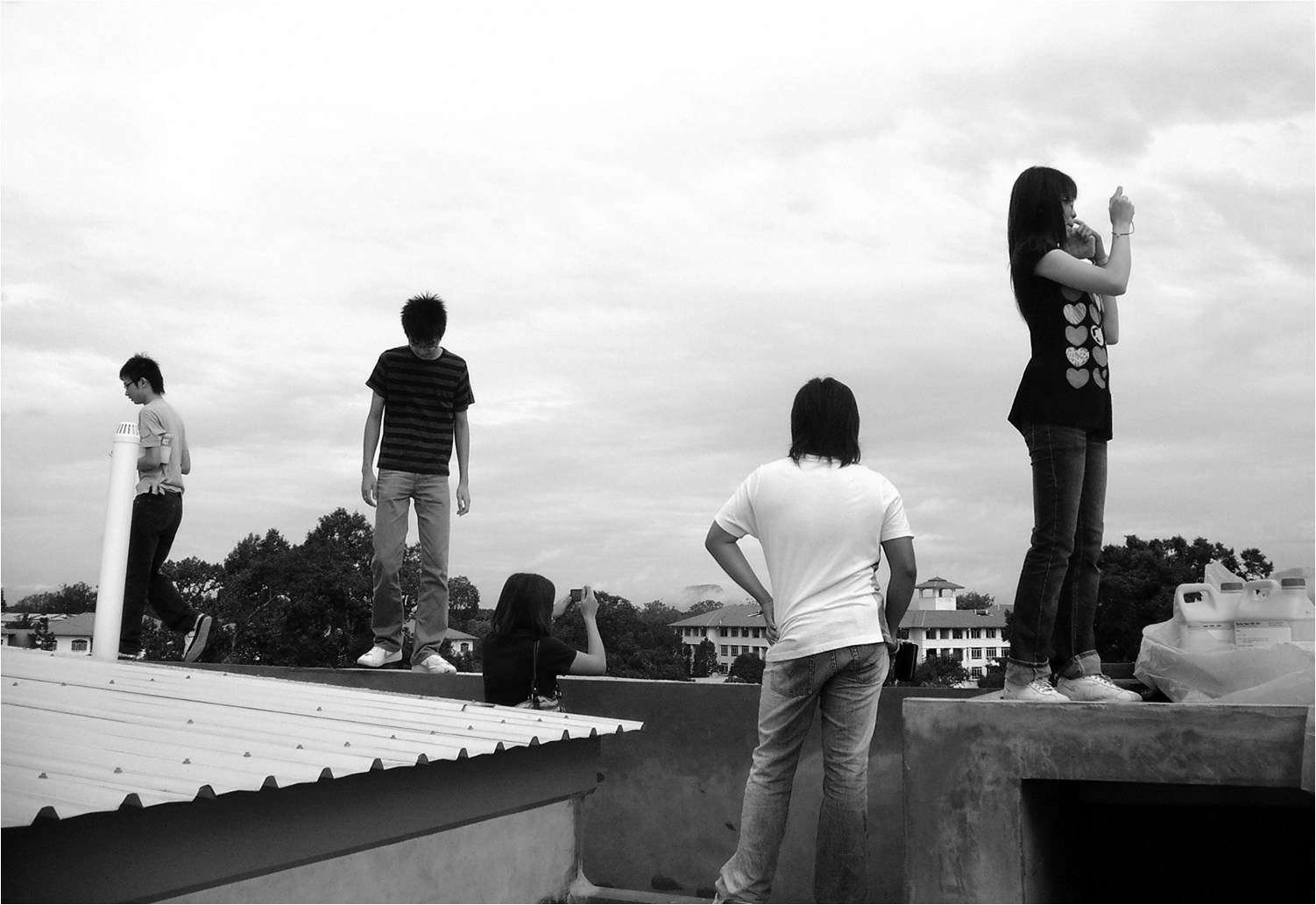

-Other offices encourage their interns to participate in competitions – this is a good way for them to re-learn design thinking, to develop a competitive edge and their design portfolio. And if they win prizes or accolades, those serve as extra motivation.

-Competitions and pro-bono/CSR work are a good platform to level the hierarchy in the office – everyone is invested with equal say. It is also an excellent way to learn new aspects of design such as local history and culture, politics, socio-economics, etc

> Pay them an allowance, and insist they spend their lunch money to eat with their colleagues. They learn so much from each other.

> If possible, pay them a decent wage.

* Some interns would negotiate or indicate an expected salary. I have had one who negotiated a salary and housing package (she was not from Kuching); we treated it as part of her education and reached a mutually satisfactory conclusion.

> See mentoring interns as an investment: in a small spectrum, it is groundwork for your practice. Some interns graduate and join you (as the negotiating intern did when she graduated from her Part 2). In a broader spectrum, it can be seen as an investment in the next generation of architects in our country.

In the early 2000s, there was a shortage of local firms wanting to take on interns – “what are they able to do?”, and “I don’t have time to teach” were the remarks frequently asked when we try to place our students

*I was tutoring at United College, Sibu then; now called Kolej Laila Taib.

That has changed greatly since then with many local firms seeming to make the internship programme part of their office culture. Design Network Architects (DNA), IDC Architects, MNSC Architects and PDC Design Group are among the many local practices with far ranging impact not only with local students but ones from West Malaysia and beyond.

THE SCHOOL

> Architecture schools often have difficulties with the placement of their students in internship positions; this is often due to the lack of a ‘working relationship’ between schools and the profession.

This can be alleviated by several simple measures:

a. Working with the local chapter of PAM – to set up platforms for firms to express interest in taking on interns; with guidelines on responsibilities and expectations.

b. Having lecturers/tutors who are practitioners – so that they can provide a informal link to local practices.

c. Having practitioners as external assessors at university design reviews – as a platform for students to have direct access to the profession.

d. Having a yearly or bi-yearly student portfolio exhibition – this can be online and is an effective way for the university to showcase the students’ capabilities. If done through PAM, the outreach can be very comprehensive.

e. Returning interns to give an account of their practical training experience – a simple word-of-mouth review and postmortem of their practical experience so that juniors can learn which firms to apply for.

CONCLUSION

The notion of ‘practical training’ or a ‘gap year’ used to be an option – something to take on if the opportunity arises. It is rare to meet a graduate who has not trained in an architect’s office before graduating – it is an essential part of the journey. Not to collect merit badges like a Boy Scouts but to try different practices to see which nurtures your passion in architecture more. And then use that to frame your own design thinking to drive the direction of projects in school, and later in your place of work and career.

If that is not a good enough incentive, consider that employers rarely pick candidates without some sort of relevant work experience. It is common sense to want someone who has experienced work life before – they are easier to train and might bring in positive aspects from other practices.

End

By Min and Tay Tze Yong