Article by: Ar. Wee Hii Min

This is the fourth instalment in our series of articles based on our observations as industry assessors at design crits to discuss:

1. What we observe at the review sessions

2. What we would like to see the students do differently

3. What the school/ profession can do to enhance the learning experience

We divided the articles into various categories based on the marking criteria commonly found in architecture schools. We have covered the first category, which is RESEARCH and are now at DESIGN, divided into the following sub-headings:

■ critical response

■ innovation

■ context

■ development

■ compliance with regulations

In this article, we will discuss Critical Response and Innovation, and contrast it with Compliance with regulations, which is a subject that requires its own careful response. Tip the scales too heavily towards Compliance with Regulations.

CRITICAL RESPONSE

When the student is given a project brief, he should understand that this is a catalogue of requirements (usually physical) and wish-list items (usually emotive), which he can (and should) challenge. More teachers can encourage this type of critical response; to dissect and re-construct the brief.

An example:

In April 2016, the National Trust for Scotland (NTS) announced that it was seeking an architect for an ‘innovative and exciting’ (emotive requirements) temporary visitor centre at Hill House in Helensburgh. The project which was scheduled for completion in 2017 will boost visitor numbers and overhaul ‘outdated’ facilities at the Charles Rennie Mackintosh-designed landmark. The building also suffers from water ingress and a significant restoration programme is expected to see the entire landmark surrounded by scaffolding in the future.

According to the brief: ‘We wish to appoint an architect to design a statement temporary building which complements the Hill House and which is so exciting in itself that it significantly raises the profile of the property and increases visitor numbers to the site.’ The new building will include an admissions area, shop, kitchen, toilets, offices and interpretation displays. (physical requirements). *1

Applicants must submit a single-page narrative confirming their interest in the project and detailing their design approach and previous experience. Selected applicants will then be invited to tender before a shortlist is drawn up for interviews. *2

Note to students:

1. Briefs ought to be challenged and questioned; otherwise, you will end with a studio of similar design schemes like obedient children afraid to speak out.

2. See how concise the entry criteria are for such a key project; strong design ideas are often easy to explain and understand. Often the scheme is given a name, which aptly sums up its intent, or outlook.

Fig. 1: The Hill House in Helensburgh by Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Fig. 2: The winning entry was from Carmody Groarke treated the restoration process and the Hill House as a museum artefact.

Fig. 3: A huge, abstracted garden pavilion whose walls are covered entirely with a stainless-steel chain-mail mesh

Fig. 4: An elevated walkway which loops around and over the Hill House provides a remarkable visitor experience

CRITICAL RESPONSE + INNOVATION

The winning entry was from Carmody Groarke; a London-based architectural practice founded in 2006 by Kevin Carmody and Andy Groarke. Instead of designing a visitors’ centre as the brief called for, they opted instead to design a huge, abstracted garden pavilion whose walls are covered entirely with a stainless-steel chain-mail mesh. This semi-permanent enclosure provides a basic ‘drying-room’ shelter to the original house whilst its rain-soaked existing construction is slowly repaired. This delicate enclosure also allows uninterrupted views, night- and-day, to-and-from the landscape to Mackintosh’s architectural icon.

The Hill Box (as the scheme was called), would provide a safe, sheltered construction working territory, the “museum” will provide a remarkable public visitor experience of the conservation in progress, achieved by an elevated walkway which loops around and over the Hill House at high level.

Note to students

Despite seemingly going against the brief the winning scheme nonetheless fulfilled many of the requirements of the brief, by the introduction of a ‘game-changer’ – which was to treat the restoration process and the Hill House as a museum artefact.

Imagine if we had carried out a similar exercise with the recent Sarawak Museum restoration, and be able to look up-close at different levels of this local landmark, and continue to visit the exhibits by peering through the windows. Moreover, if we charge the visitors, this means that the museum is already earning its keep with undergoing restorations.

CRITICAL RESPONSE + INNOVATION + COMPLIANCE WITH REGULATIONS

Another example:

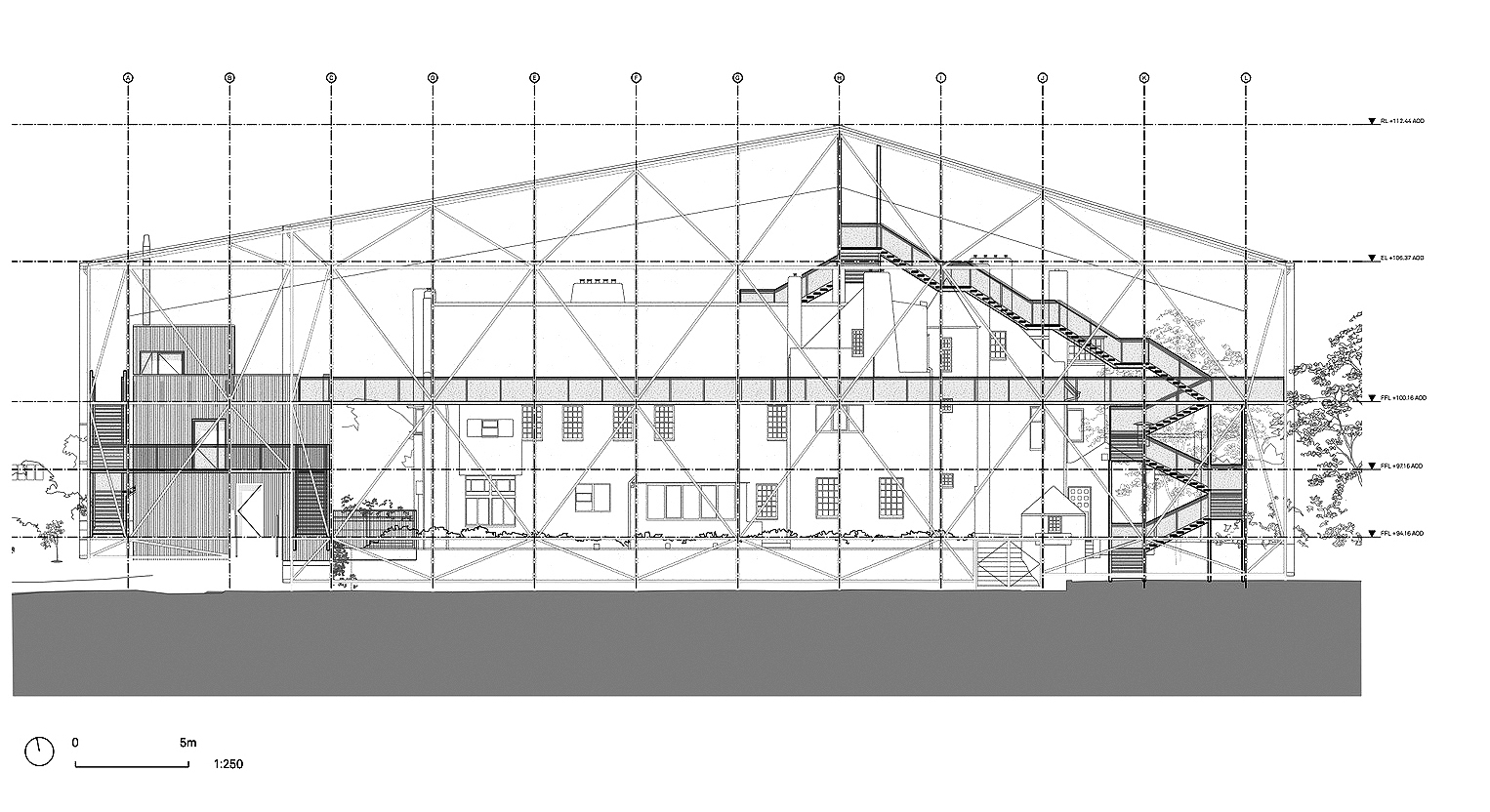

MVRDV’s Wozoco (1994 – 1997) is located in a garden city west of Amsterdam. It is a building of 100 homes for the elderly; its extravagant profile was a result of a zoning regulation, which limited the number of apartments per block to 87 units. This was to ensure that each tenant was promised good natural lighting.

When the client requested for 100 units per block, it was clear that the additional 13 units would have to occupy another floor – yet another constraint the client wanted to fight. A half-joking solution, presented at the first meeting suggested that the additional units were ‘glued’ to the outer side of the main building volume drew surprising attention. The client saw the potential and MVRDV rose to the challenge… and the 13 additional units were cantilevered from the side of the main structure. WoZoCo continues to be a favorite amongst architectural enthusiasts (including members of our PAMSC study tour group) who travel to the Western Garden Cities to see the ‘hanging houses of Amsterdam’.

Note to students

Obstacles and constraints sometimes work to the design’s advantage, for us to come up with solutions that surprise our clients, the end-users and even ourselves.

Fig. 5: Sarawak Restoration – under wraps

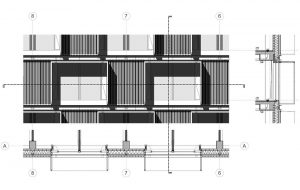

Fig. 6: MVRDV’s Wozoco – its extravagant profile was a result of a zoning regulation

Fig. 7: A half-joking solution suggested that the additional units were ‘glued’ to the outer side of the main building

Fig. 8: Structure is hidden inside the main block, found under the wood sheathing

Reference:

https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/competitions

https://www.carmodygroarke.com

https://www.mvrdv.nl/projects/