Article by: Ar. Wee Hii Min Published on: Intersection News - PAMSC Circular 4 (23.10.2020)

This is the second instalment in our series of articles based on our observations at design crits and workshops in local universities. It is written with the primary objective of promoting discourse amongst fellow architects and as reference material for our student readers. The topics of our articles are loosely based on the sub-headings in the marking sheets.

RESEARCH

Following on from Site Analysis (Architecture Education 1.1), the student will then conduct research on the project. Assuming that much of the research on the geography of the site was carried out as part of the site analysis, the student now focuses on researching the building typology and the technologies and logistics involved in its development and innovation.

This used to be a task carried out in the library – looking through reference books, magazine articles, and students’ theses. Searching through microfiche for relevant news articles, and writing to other libraries for excerpts when your university library does not have the much needed texts. This was in a bygone era; pre-Google, these days ‘research’ is simply a click and a key word away.

Therein lies the problem – the internet offers up some many options, much of which is visual. Architects (and architecture students) are visual creatures; easily seduced and distracted by a striking image of a building such that ‘Precedent Studies’ is diluted into ‘Relevant Images’. Even seasoned architects fall victim to the seduction of Pinterest and the quest for Instagram-able images, what more to say a student hungry for inspiration two days away from project submission.

There are no shortcuts when doing research, and reading is part of the task in hand.

Note to students Read broadly at the beginning of your research, summarise your findings and record your sources so you can track it later. (or discard it, not everything that you read will find its way into your project – that is part of the research process) Reading broadly adds depth to your research and complexity to your design.

Fig. 1: Kanchanjunga Apartments, Mumbai. Charles Correa 1983.

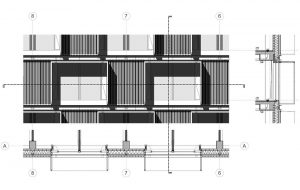

Fig. 2: Correa pushed his capacity for ingenious cellular planning to the limit, as is evident from the interlock of four different apartment typologies varying from 3 to 6 bedrooms.

Imagine a student designing a residential housing tower, she is fascinated with the form of Charles Correa’s Kanchanjunga Apartments, and used that as a point of reference for her design. However, unless she delves beyond the skin, she would fail to learn about:

- the Indian master architect’s skill for cellular housing

- and fondness for using changes in floor levels to define spaces within an open plan

- which is likely influenced by the Modern Masters such as Le Corbusier

- whom Correa referred to in his building cross section (from Unit d’Habitation)

- and that the deep set garden terraces of the Kanchanjunga Apartments are actually a modern interpretation of the verandas in the Indian bungalow.

These brief points only hint at the depth of research that Correa must have done; each is a catalyst for further reading and research, which can benefit other aspects of the student’s education.

Much that is successful in a project is un-seen, but felt and experienced. It is a difficult quality to teach, and even educators struggle to understand this. In a recent design forum which I attended, a senior lecturer asked Sri Lankan architect, Palinda Kannangara after his hour-long lecture – ‘what is it about your architecture that makes it Sri Lankan?’ I cannot remember Palinda’s exact answer, but it was along the lines of the unseen qualities which the Sri Lankan architect and his clients understood:

- Stillness and simplicity – in taking the time to approach, arrive, enter, and experience a building, and the simplicity of the materials used which often included what was already there; bed-rock, trees, a stream, the side of hill.

- Nature (and the natural) –at ease in allowing time to mark the surface by changing its colour, to change its texture with moss, in allowing the rain to come into the house; verandas are deep for that purpose, and we can always move the deck chairs into the house.

- Sufficiency – in the sizes of the rooms and spaces, in the usage of material, and the omission of certain building elements if it did not enhance the experience – why do we need doors if a doorway is enough to draw a line between two spaces, and it frames a view?

Note to students Design is about improving the experience for people; the end-users.

Fig. 3: Stillness and simplicity

Fig. 4: At ease with nature and the natural – photo courtesy of Palinda Kannangara Architects

Perhaps there is a deeper reason for this way of thinking and behaving, one that is rooted in their history. History therefore is an important subject in design research; a study of the past – specifically the people, societies, events and problems of the past – as well as our attempts to understand them. It is a pursuit common to all human societies.

by Min